Mass and Veneration

Monday, November 17, 2025

1:00 pm

St. Ninian Cathedral, Antigonish

This visit in our diocese is part of an eastern Canadian tour by Martyr’s Shrine in honour of the Jubilee year.

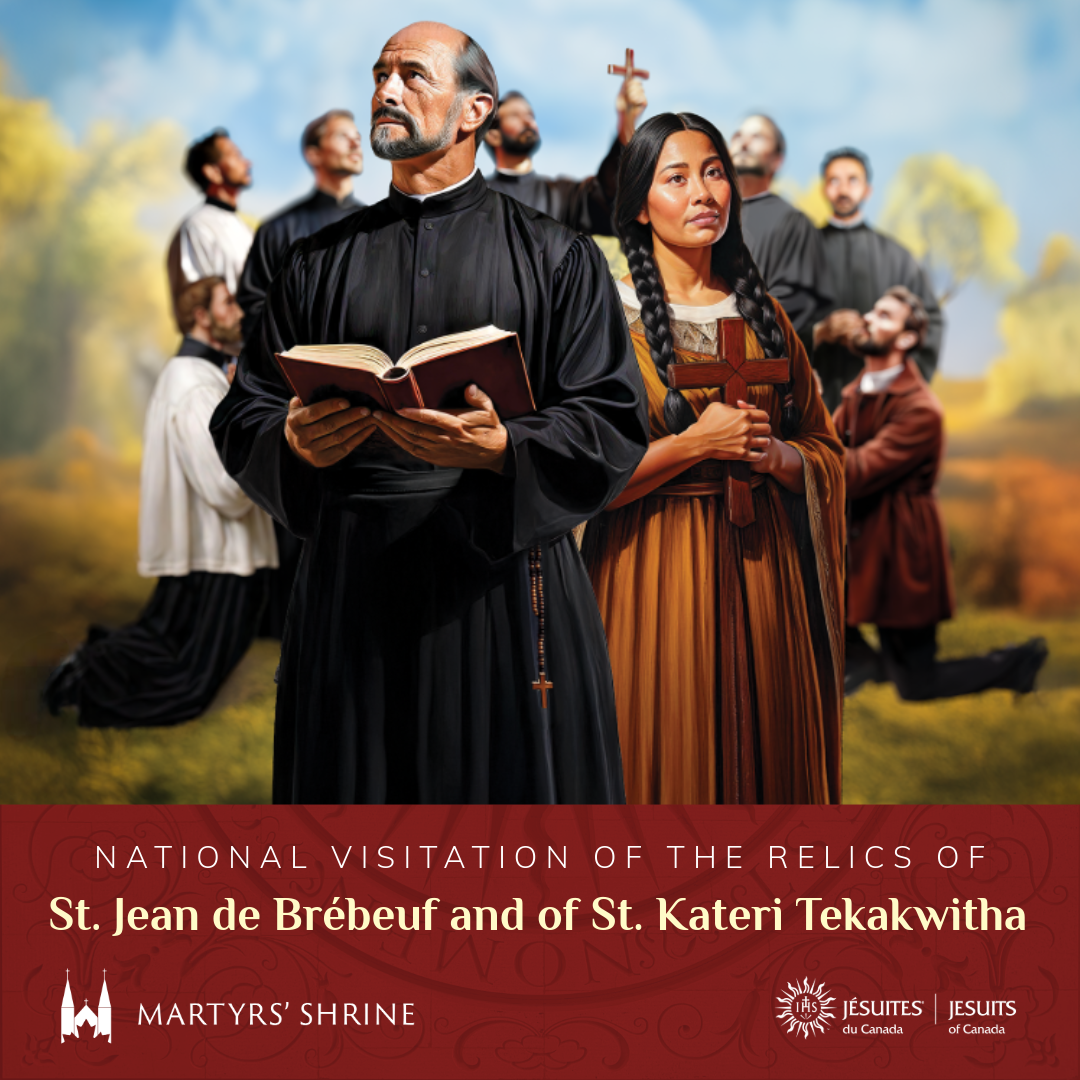

The major relics of St. Kateri Tekakwitha and three Canadian Martyrs: St. Jean de Brébeuf, St. Charles Garnier and St. Gabriel Lalemant, have been travelling across Canada since late 2024 in celebration of the Jubilee Year of Hope.

Learn more about the relic tour in North America

For the past 100 years the Canadian Martyrs relics have resided principally at the National Shrine to the Canadian Martyrs in Midland, Ontario. The devotional tour is bringing the relics to parts of Canada enabling those unabe to travel to the shrine to be a Pilgrim of Hope in the presence of these great saints, “and receive the graces of healing and reconciliation for themselves, their families, and our country.”

Who were the Canadian Martyrs?

The eight Canadian or North American Martyrs were six French Jesuit priests and two lay companions, who lived and worked among the Wendat or Huron people in the early 17th century. The Jesuits were St. Jean de Brébeuf, St. Gabriel Lalemant, St. Isaac Jogues, St. Charles Garnier, St. Noël Chabanel, St. Antoine Daniel, and the donnés were St. René Goupil and St. Jean de Lalande. Five were martyred in the region known as Huronia or Wendake in Ontario, and three were martyred in the country of the Iroquois in what is now upstate New York. They were beatified (declared “blesseds”) in 1925, canonized as saints in 1930, and declared the co-patrons of Canada in 1940. They are to date the only canonized martyrs of North America.

St. Kateri Tekakwitha, the first indigenous North American saint, was canonized in 2012 and is a beloved patron of the First Nations peoples.

St. Kateri Tekakwitha, the first indigenous North American saint, was canonized in 2012 and is a beloved patron of the First Nations peoples.

She was born in 1656 in the Mohawk village of Ossernenon (now in the State of New York) the daughter of an Iroquois chief and Algonquin Christian mother. When she was four, her village was decimated by smallpox: Kateri lost both of her parents, and was left physically scarred and visually impaired. Tekakwitha means ‘she who gropes her way’, a name she was given due to her way of moving, due to her eyesight.

In 1675 she met French missionaries at a mission while she and her village hid from French soldiers. She asked to be baptized and was given the name Kateri, a variation of Catherine, for Saint Catherine of Siena. Kateri was persecuted by her family and villagers for refusing to work on Sundays and her devotion to Mass. She eventually moved to a Christian village in what is today known as Kahnawake, where she made her First Communion on Christmas 1677. She refused all offers and pressures to marry, and held a dream of founding a First Nations community of consecrated life. After a lifetime of health issues, she died at age 24 on April 17, 1680.

St. Kateri Tekakwitha was canonized by Pope Benedict XVI in 2012.

Learn more of St. Kateri Tekakwitha

Why a relic tour?

2025 is a Jubilee Year for the Catholic Church. Martyrs’ Shrine is an official pilgrimage destination for the Holy Year but is only accessible to those who can travel there. The purpose of the relic tour is to bring the relics to places where people might not easily travel to the Shrine.

2025 is also the 100th anniversary of the beatification of the Canadian Martyrs (1925) and the 400th anniversary of St. Jean de Brébeuf’s arrival in Canada (1625).

What is a relic?

A relic is a physical object associated with a saint, such as a bone or a piece of clothing belonging to the saint.

Relics are divided into three classes. First-class relics are physical artifacts from the saint’s body, usually bone or bone fragments; second-class relics are items that belonged to or were used by the saint, such as clothing or books; third-class relics are items, such as a rosary, a piece of cloth, or a prayer card, that have been touched to a first or second class relic.

Why do Catholics honour relics?

Nearly every human being cherishes objects that link us to our family members or ancestors. People keep physical mementos, pictures, a lock of hair, even funeral urns to connect us to those we love. Catholics have always honored the relics of the saints as heirlooms of our spiritual ancestors; moreover we believe that relics are “sacramentals”, or holy objects that are vessels for special graces and blessings.

Is there a basis for devotion to relics in Judeo-Christianity?

During the time of the early church, Christians experienced miraculous healing associated with the bones of the dead martyrs. This was no surprise to them, since from the times of the Old Testament the bones of the dead were occasions of healing. Moses carried the bones of Joseph out of Egypt (Exodus 13:19). Men placed a dead man into the tomb of Elisha and the dead man came to life when he touched the bones of the prophet (2 Kings 13:21). In the New Testament, people touched cloth to St. Paul’s hands, then they touched that cloth to the sick and they were healed (Acts 19:11). St. Ambrose and St. Augustine wrote about personally witnessing miracles after a martyr’s relic touched a sick man. Throughout Christian history relics have been venerated and people have pilgrimaged to pray with them.

What are the relics of the Canadian Martyrs?

The major relics of the Canadian Martyrs are the skull of St. Jean de Brébeuf and bones of St. Gabriel Lalement and St. Charles Garnier. Of the eight martyrs, they are the only three of whom relics survive. The relic of St. Kateri consists of bone fragments and is to our knowledge the largest relics outside of her tomb in Kahnawake. All these relics reside in the church at Martyrs’ Shrine.hey are kept at the National Shrine to the Canadian Martyrs, located in Midland, Ontario, visited by over 100,000 pilgrims each year. This is the first time the relics have left the Shrine to go across Canada.

Who was St. Jean de Brébeuf?

The most well-known of the Canadian Martyrs is St. Jean de Brébeuf. He came to Canada in 1625 and lived in Wendake or “Huronia” for nearly 25 years. Known for his gentleness, kindness and strength, he quickly earned the friendship of the Wendat and was especially close to the Bear Clan. He was the first European to learn the Wendat language, wrote a French-Wendat dictionary, and composed Canada’s first Christmas hymn (The Huron Carol). A mystic with a deep prayer life, Brébeuf had dreams and visions of the saints and once of a large cross in the sky. During the 1649 invasion of Huronia by the Iroquois, Brébeuf was captured with his companion St. Gabriel Lalemant on March 16, 1649, and taken to the village of St. Ignace where they were ritually tortured and killed.

How were the relics preserved?

The bodies of Brebeuf and Lalemant were recovered a few days after their deaths and brought back to the mission of Sainte-Marie. Some of the bones, including Brébeuf’s skull, were preserved, and the rest of their mortal remains were buried in the ground, where they remained for more than 300 years. The surviving Jesuits and Wendat then abandoned Sainte-Marie, built rafts and went to an island in the Georgian Bay where they tried to build a more protected mission. After a brutal winter, they realized the mission in Huronia was over, and they returned with the relics to Quebec, where the descendants of the Wendat live to this day. The relics went to the Brébeuf family in France, but returned to Canada later, where they were cared for by the Jesuits and the Augustinian sisters of Quebec.

Were any of the Wendat (Hurons) also martyrs?

Although they are not officially canonized, the character and faith of the Wendat Martyrs of Huronia is without dispute. Several Wendat, for instance, were martyred at the same time as Brébeuf and Lalemant, professing their faith until they died. Joseph Chiwatenhwa was among the earliest of the Wendat to ask for baptism. He was the first Indigenous person to pray the “The Spiritual Exercises”, the silent retreat written by St. Ignatius of Loyola. He and his wife Marie Aonetta became Canada’s first lay church leaders and catechists. He was called “the apostle with the apostles” by St. Marie de l’Incarnation and helped prepare the baptisms of more than 3,000 of his own people. He was killed in a field near his village on August 2, 1640. Pope John Paul II said Joseph and his family “lived and witnessed to their faith in a heroic manner.” There is interest in Canada in promoting their eventual canonizations.

Who was St. Kateri Tekakwitha?

St. Kateri, informally known as “the Lily of the Mohawks”, was born in 1656 to an Algonquin mother and Mohawk (Iroquois) chief in the village of Ossernenon in present-day upstate New York. She lost most of her family to a smallpox epidemic, and herself recovered with scars on her face. At the age of 18 she met the Jesuit priest Jacques de Lamberville, and shared with him her desire for baptism, which she took a year later. After undergoing harassment in her village, she moved to the Christian Mohawk village of Kahnawake (south shore of present-day Montreal). She took a vow of virginity and devoted herself to prayer and to helping the people around her. She struggled with poor health, and when she died on April 17, 1680 at the age of 23 or 24, her last witnessed words were “Jesus, Mary, I love you.” She purportedly appeared to three individuals after her death. More than 300 books have been written about her extraordinary life. She was beatified in 1980 and canonized in 2012. St. Kateri is the first indigenous person to be canonized as a saint and is venerated by First Nations peoples across North America. Her tomb is at her shrine in Kahnawake, Quebec. The home of her relic is at the Martyrs’ Shrine.

Is there a connection between the relic tour and the Truth and Reconciliation movement in Canada?

There is no formal connection, but there is a desire for more prayer and intercession for the ongoing process of reconciliation, of repairing relations between Canada’s Indigenous and non- Indigenous peoples. 2025 marks ten years since the historic Truth and Reconciliation Commission report was issued with its recommendations. We believe that true healing will come not from our power alone, but with the help of the saints who continue to work for the good of the world. Since the Canadian Martyrs loved the First Nations people so greatly, they are fitting saints to pray to for this intention. St. Kateri is the patron saint of First Nations people (and of ecological integrity), and her love for others and for her faith makes her also a fitting saint for this purpose.

What is Martyrs’ Shrine?

The National Shrine to the Canadian Martyrs is the custodian of the major relics of the Canadian Martyrs, and is located in Midland, Ontario, a two-hour drive north of Toronto. It is served by the Jesuits of Canada since it opened in 1926. Millions of people have visited the Shrine over the decades. In 2026 the Shrine will celebrate its 100th anniversary. Many healings have been reported and documented. More than 35 ethnic and cultural pilgrimage events take place each summer. Week-long walking pilgrimages are organized from Toronto and other locations. Many youth and young adult groups visit the Shrine each summer. Pope John Paul II made a historic visit to the Shrine on September 15, 1984. The Shrine is open to the public only six months of the year (May to October). Next to Martyrs’ Shrine is the “living museum” Sainte-Marie among the Hurons, a reconstruction of the original mission and a National Historic Site of Canada, operated by the government of Ontario.

Learn more about the National Shrine to the Canadian Martyrs

Who are the Jesuits?

The Jesuits, or The Society of Jesus, is a religious order founded by St. Ignatius of Loyola and his companions in 1540 to serve the needs of the Church. Members take vows of poverty, chastity and obedience. Numbering around 14,000, Jesuits are found in 112 countries. In Canada, around 200 Jesuit priests and brothers work from coast to coast, engaged in evangelization and pastoral ministry, in education and research, work in hospitals and conduct retreats. They also do social and humanitarian aid throughout the world.